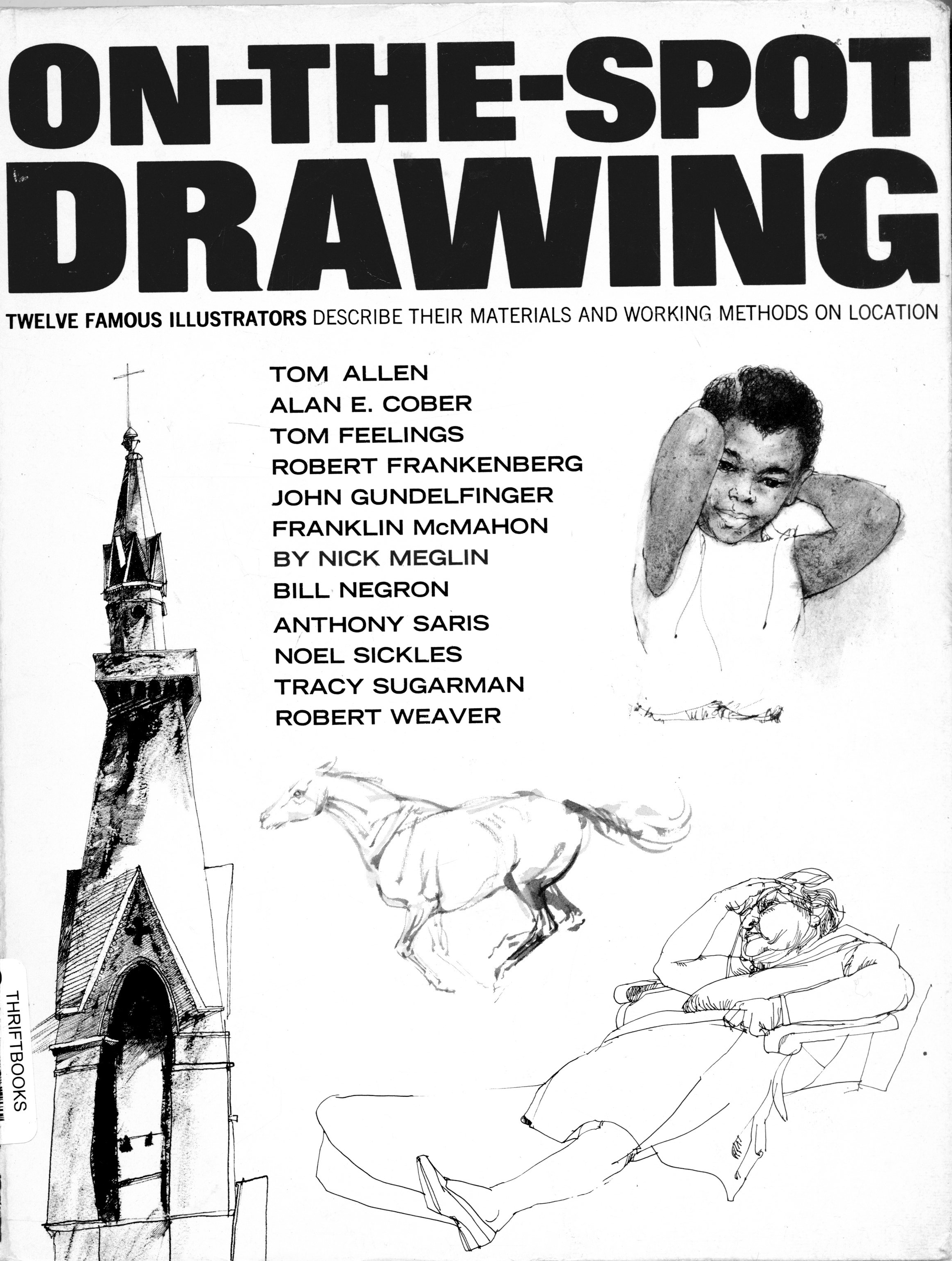

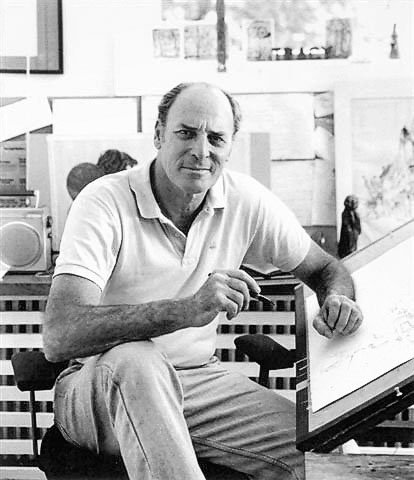

Drawing On the Spot: Twelve Illustrators Describe Their Materials and Working Methods on Location by Nick Meglin was published in 1969, and that was a time when a number of prominent illustrators were regularly commissioned to do visual reportage for magazines. Looking at the list of artists interviewed in the book, we see some very important and influential artists. Back then, magazines like Fortune would feature lots of illustration – much of it created from on-site investigation and creation. Sports Illustrated was, well, illustrated, art least partially. And publications such as Holiday and Look which no longer exist, sent illustrators on assignment as correspondents as well. And they were not the only ones.

Nowadays, we’re seeing a resurgence of illustrators working on location, although the assignments are still quite slim. It’s interesting to see how many great young illustrators of reportage there are in England right now. But in the US, there are only a few who have a busy reportage practice.

What we do know is that the internet has fostered the huge growth in the popularity of sketching on location and charing the work online. Artists and designers are acting as correspondents of their own lives. Urban Sketchers (which I’m affiliated with) is approaching its 10th anniversary, and it has fanned the flames of enthusiasm.

So perhaps it’s a good time to revisit Drawing On the Spot. In the first of what I hope to be a series of book reports, I cull the book for some nuggets of wisdom from a number of artists who worked “outside the box” – their studios that is, to create great works as both artists and correspondents. What follows are highlights from the chapters on each artist and a reproduction of their work from the book or the internet.

Tom Allen

“The only sacrosanct rule of art for me is personal involvement. All other rules can be – and have been- successfully broken. An artist must be intensely involved with his subject in order to give it his particular insights and convictions – his point of view.”

“Without total involvement there would be no art, only pictures.”

“There may be several aspects of a scene that stimulate my interest. Sometimes the stimulating factor is the mood, or an emotional response, or sometimes it’s the the activity in a scene. More often it’s the elements of design in a scene that stimulates me. I look for shapes and compositions formed either by things and people, or by light and dark.”

Alan Cober

“A drawing should have a life of its own”

Tom Feelings

“For me, it’s not art for art’s sake, it’s art for my sake.”

“It’s important for an artist to depict the things he feels strongly. Growing up in a black community in Brooklyn and yet not seeing enough drawings and paintings that say enough about the people and places right outside my door – the things I see and feel every day – convinced me of the need to portray this contemporary scene. I deeply feel that this direction is extremely important for the black artist, for his own development and search for originality.”

“If you’ve never felt insignificant, you don’t have to search for your significance as I did. I returned to the United States (from working in Africa) with the need to express myself as a man through my art.”

Robert Frankenberg

“There is a difference between looking and observing.”

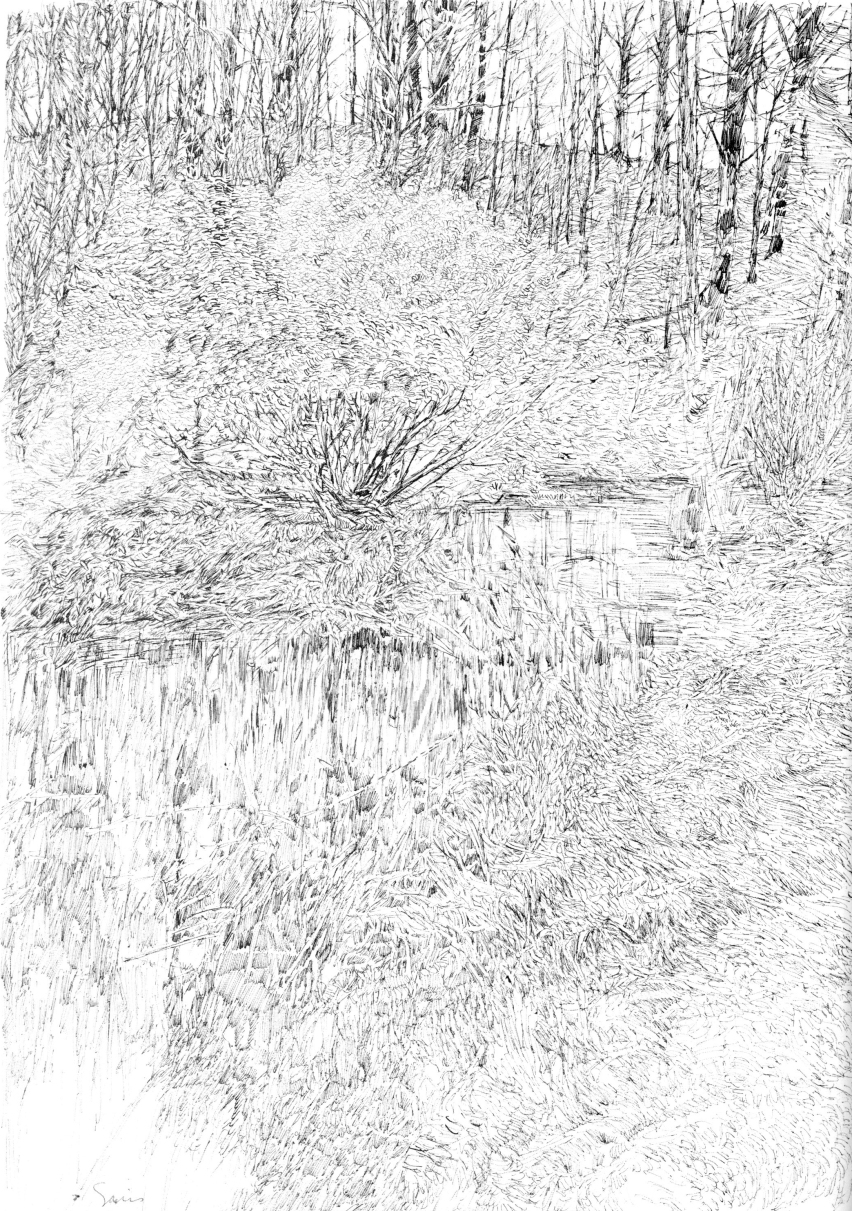

John Gundelfinger

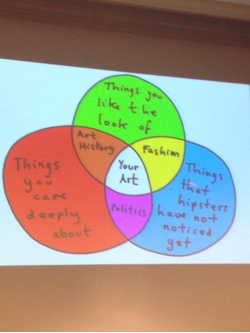

“There’s no such thing as “interesting subject matter,” what’s interesting about any subject is what you as an artist do with it. There have been interesting drawings made of what might be described as uninteresting subject matter” just as there have been flops with subjects which beg to be drawn. The fault is not with the subject but with the artist.”

“Although I believe there’s a drawing everywhere, I don’t draw everything I see. I draw only that which moves or interests me at the time. The reasons for being stimulated perhaps can be explained psychologically later on, but it’s of little concern to me. I don’t question an inspirational moment; I succumb to it. THe more you observe and draw, the more possibilities arise even from areas that most would consider dull (consider Van Gogh’s chairs, for example). The point is to draw first and ask questions later, for if the process is reversed, they’ll be too much thinking and theorizing being done and not enough drawing.”

John Gundelfinger’s drawing seem like “natural,” as if the picture were there and all he had to do was in front of him. But this can never be the case. You have to see a picture first, and the seeing is done with an educated, sensitive eye, not a lucky one.

“I never know what a drawing will look like until it’s finished. Once you do – that’s security: and security is something we can all do without in drawing. It comes from working in a particular way or style that enables you to control any subject or situation you encounter, and once you’re in control you stop learning. The nervousness and anxiety that precede a drawing are important to the end result, and certainly more of an asset to it than mannerism can ever me.

“I can learn more from my mistakes than from a drawing where everything fell into place easily.”

“It would be of little use to try to copy or imitate a good line, shading technique, or composition. Repeating a past success is no real accomplishment.”

“A finished on-the-spot drawing is a fortunate experience and should always be thought of as such. It shouldn’t be the reason you go out, for the objective is “drawing” and not “the drawing”.”

“That old cliché that “art is 10% inspiration and 90% perspiration has, like most clichés, a solid foundation. There is just no substitute for hard work…”

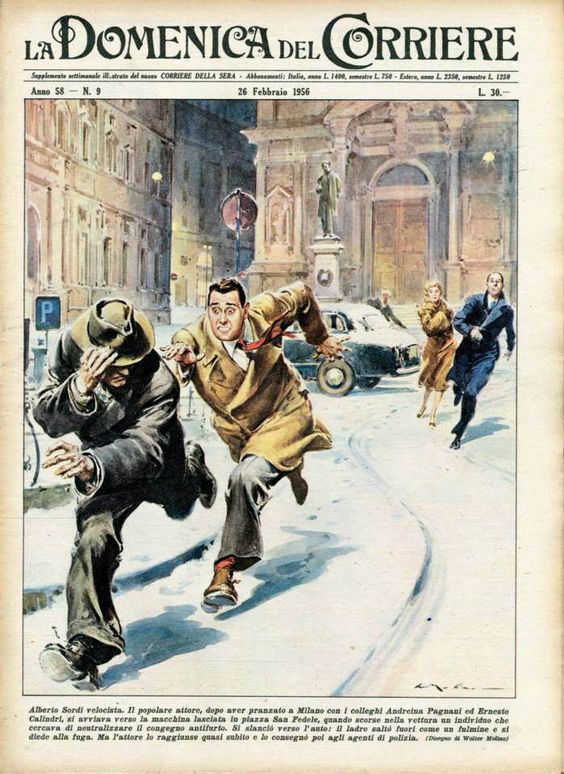

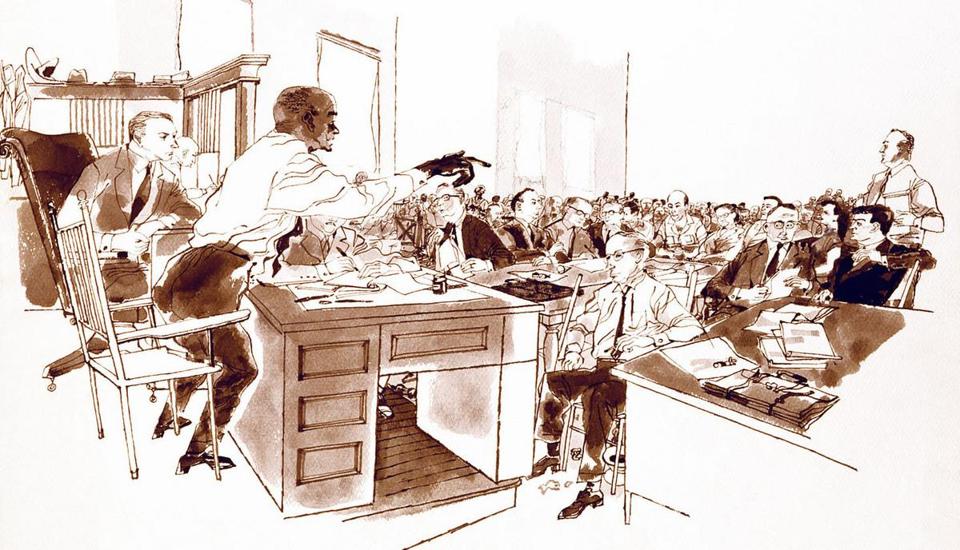

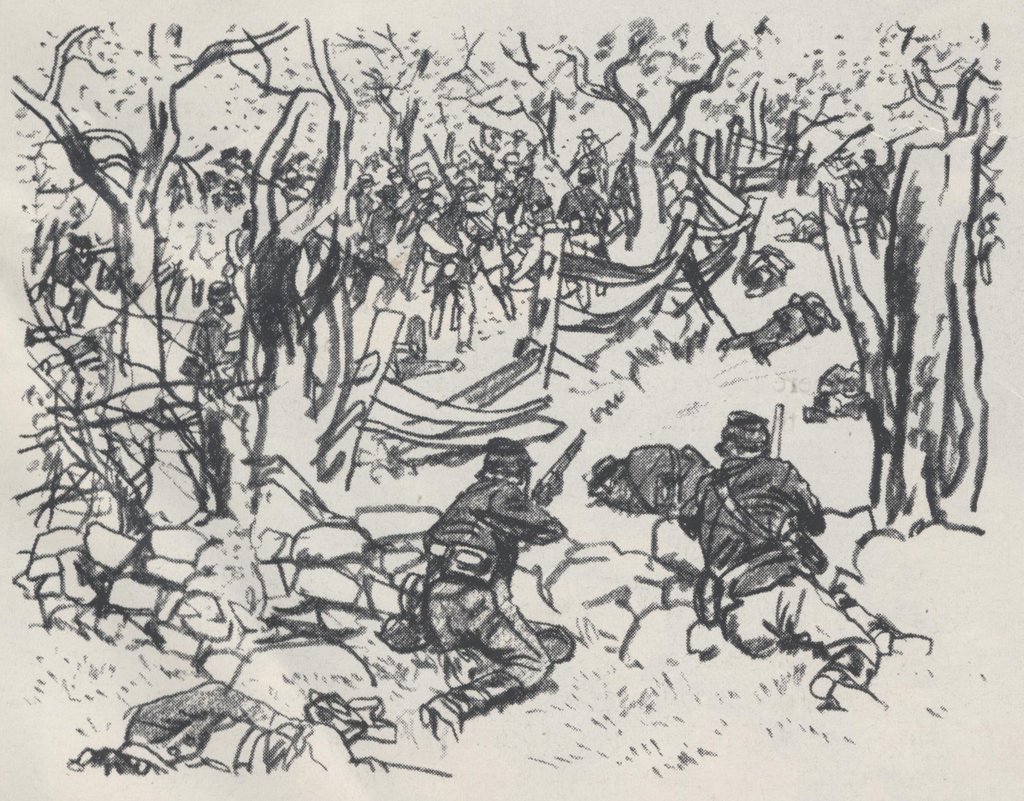

Franklin McMahon

“Most of my (reportage) work is self-assigned. I go out with an idea or premise, draw it, then submit the drawings and captions to publishers who might be interested in the story.”

On-the-spot drawing enables a type of picture coverage not ordinarily employed by photographic reportage. The cameras click “during” – seldom before or after the “decisive moment.”

“Too many artists are more concerned with the drawing process than what the drawing is all about. Materials take care of themselves if you use them simply as tools for carrying out your concepts. Once you start thinking about them you lose some of the intensity is a lot more important to the drawing than a trick line or shadow.”

McMahon isn’t searching as he draws, he’s stating.

“I don’t seek out the merely “picturesque” because everything has a way of paying off as you begin to set it down on paper.”

“On-the-spot drawing allows you to take a kind of cubist approach to the subject to the subject, drawing it from several angles in the same drawing, and drawing it as you “know” it to be rather through someone else’s angle of vision or emotional point of view, which is why I prefer not to use (other’s) photographs.”

“But most of all I believe the drawing, not just sketches or rough notations, but early commitment to the actual drawing, should take place on-the-spot. That gives artist, pencil, and subject a chance to interact.”

Nick Meglin

“I try to draw laughing eyes, not hazel eyes; or if the subject is asleep, I try to draw sleep rather than closed lids. There is a difference, and my interest is in capturing that difference.”

“Many who distort do so because they have no alternative. Distortion, then, becomes a blanket to hide the artist’s inability to produce an honest, accurate study beneath.”

“Good draftsmanship is not of an age or a “school’. It can never be dated. There always has been and will be, a place for it in the art world. What do become dated are thought processes and boundaries set up by tastes, opinions, styles, techniques, and the “acceptable” art of a particular era.”

Bill Negron

Whatever “catches” him at that instant becomes the point of emphasis.

The name of the game is selectivity. Not an intellectual selectivity, but an emotional one that responds to the moment; it cannot be anticipated nor can the effect be predetermined.

“It doesn’t make much sense to draw everything the eye can see. The greatest advantage an artist has over the camera is the ability to pick and choose. He can include or omit things at will, accenting that thing over there or fading out that street light over here. This ability to pick and choose, when combined with similar features that a camera is capable of, such as taking in a scene with a wide-angle view or coming in on something with a telescopic view, gives the artist great latitude. He can bring into focus only that which interests him.”

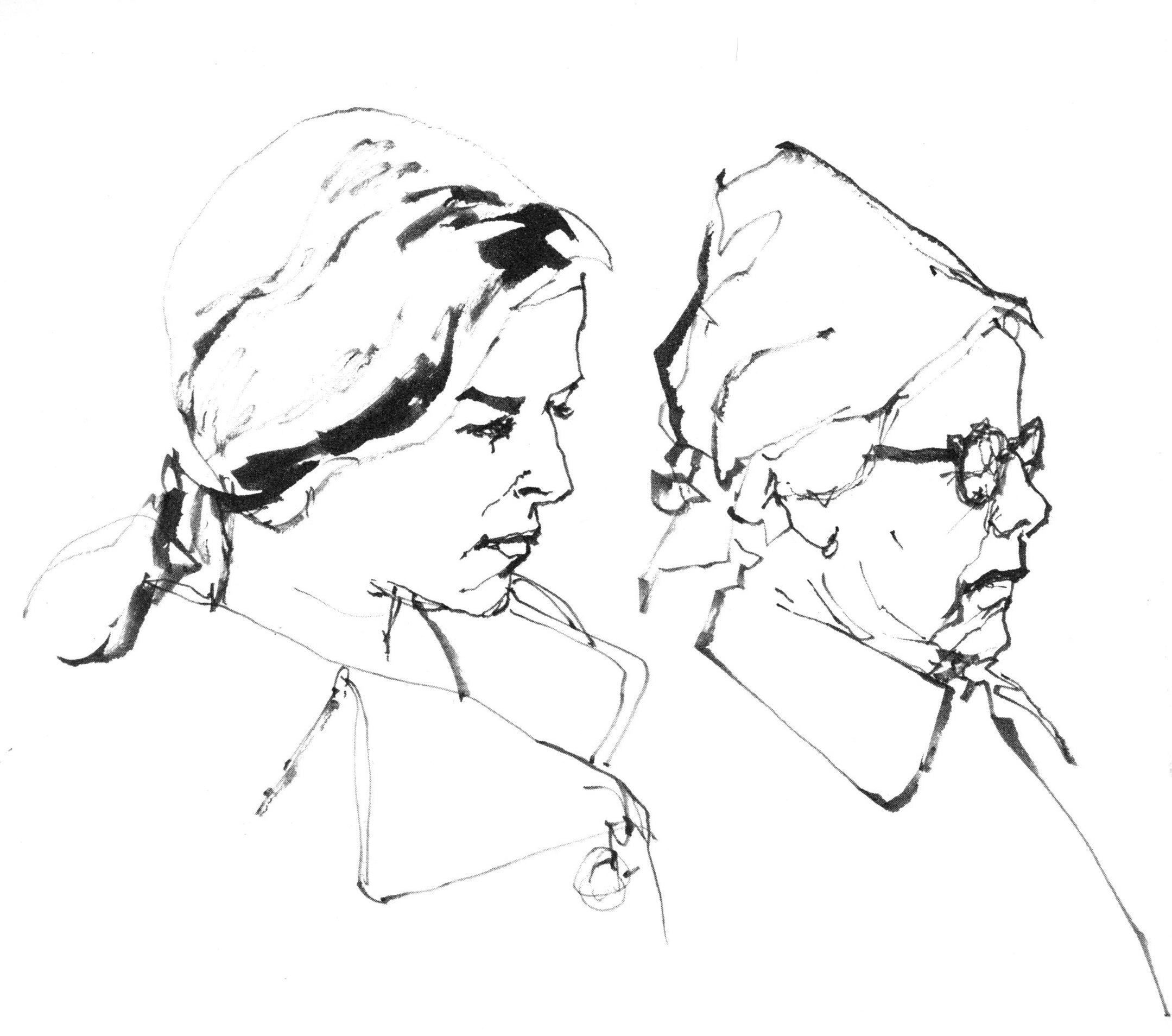

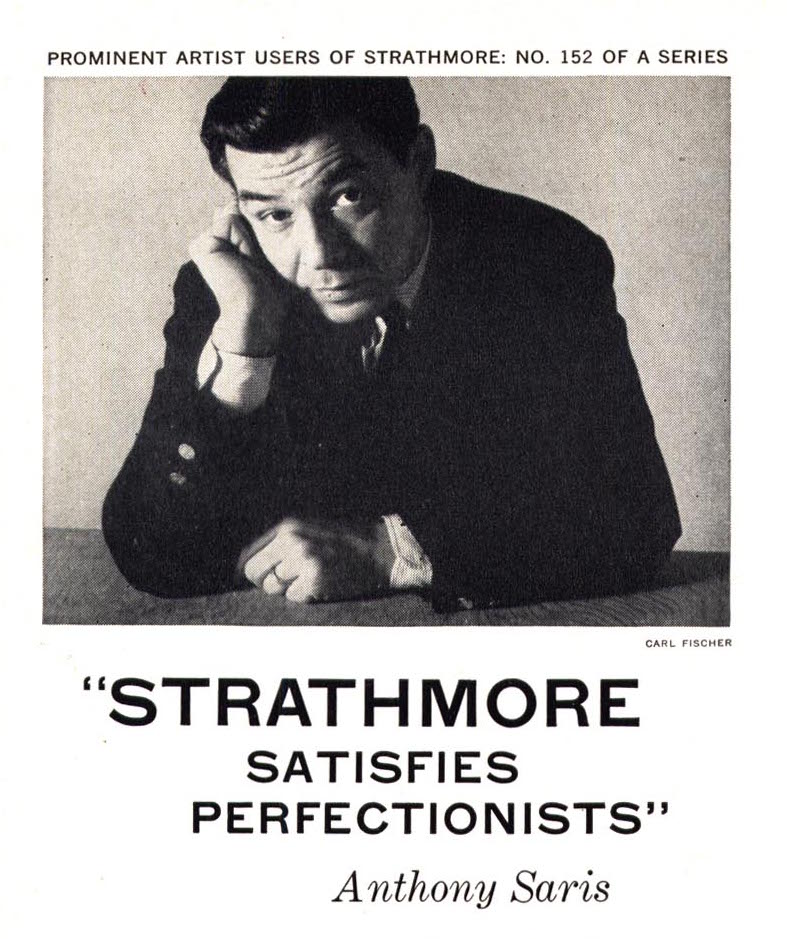

Anthony Saris

“A sketch…is much more fragmentary than a drawing, It’s a preliminary notation, often serving no purpose other than that of jotting down an impression. The pages of an artist’s sketchbook make up a graphic diary of personal thoughts, ideas, and observations; each sketch is a study, a learning process, an unfinished experiment with no predetermined use.”

“When I sketch, I’m not concerned with making personal statements or with producing a finished piece of work. I’m free of constraint and of the external pressure of deadlines, research, etc., which of course, make work especially pleasurable and relaxing.”

His motivation for drawing is far removed from his motivation for sketching, yet both are executed with the same sensitivity and with the same dedication to accuracy.

An important advantage of the objective approach is the learning which takes place.

“With on-the-spot drawing the artist encounters unpredictable situations. Once he becomes stimulated by what he sees, he’s forces to create what he feels despite his materials.”

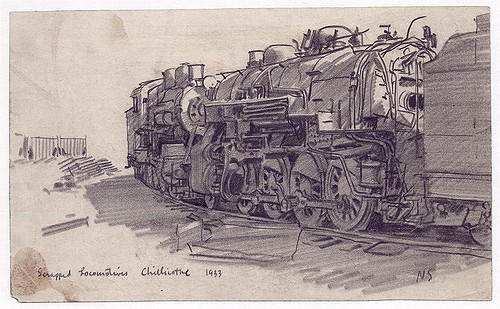

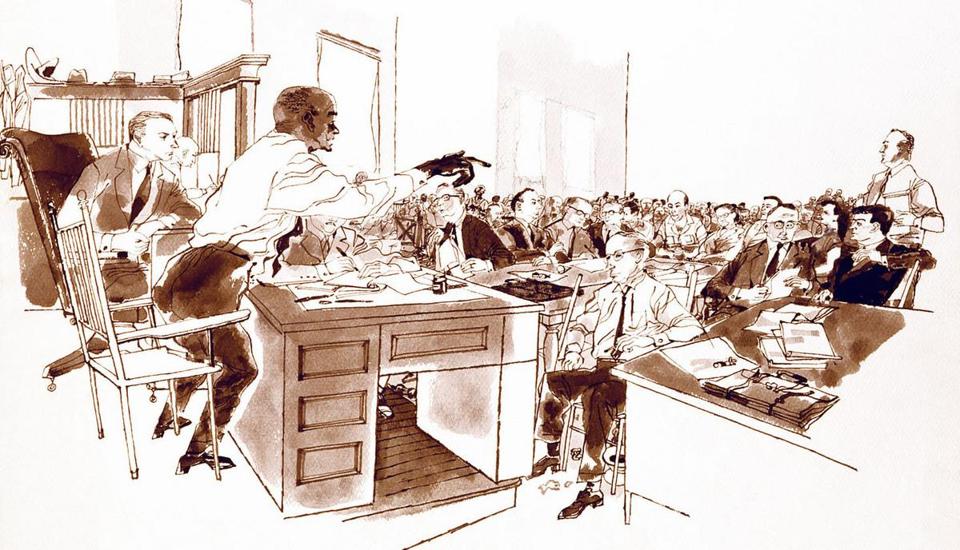

Noel Sickles

“They (reportorial and landscape artists) share a common goal – to tell the story. But hasn’t that always been the role of the artist? What is the objective of “objective art” if not to tell the story?”

“My approach to drawing has always been to communicate. That’s my chief concern. I will reduce things to basics or arrange them in a particular way, anything that will enable me to achieve the goal. An artist has the freedom to do this, his major advantage over the camera in the past and certainly in the present. Since I work rather representationally, I have to take into account all these factors. I enjoy the challenge of location drawing, and my responsibility to that challenge is to be there, on-the-spot, with all faculties alert. If the artists eyes are focused only through the camera lens he won’t be aware of what is taking place all around him, which is often of equal importance to that taking place directly in front of him.”

In the case of personal or scenic art, there are various approaches open to the preference or mood of the artist. In reportorial work, however, demands of factual representation and a high degree of identification present an altogether different list of essentials.

As Sickles puts it:

“For reportorial work, one needs a draftsman, an artist who goes beyond a literal rendering and who interprets and selects. He can often make the slightest sketch significant and can bring life, meaning, and vitality to a drawing as well as the imprint of a personal style. When I was asked to draw public figures at work in the NY State Senate in Albany, my sketches had to be just what was expected of me as an on-the-spot reporter – the Senate Hall had to look like the Senate Hall, and if a particular senator was up there on the dais addressing the assembly, then the drawings had damn well better show who that senator was. Any artist worth his salt doesn’t want to depend on a caption underneath to bail him out of a bad likeness.”

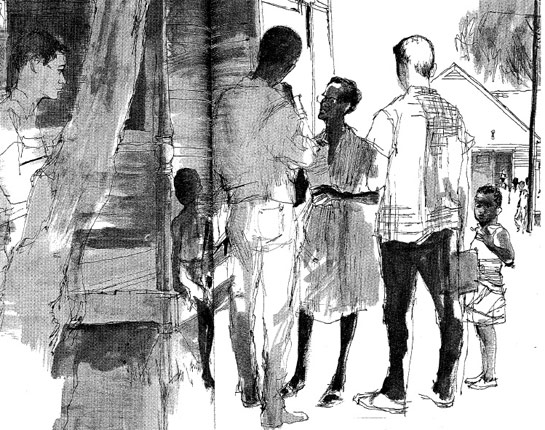

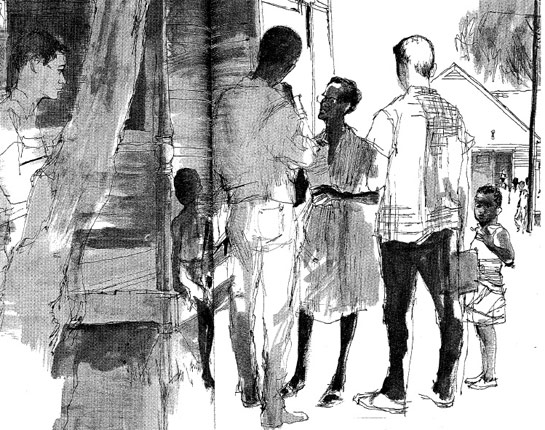

Tracy Sugarman

“To me, the most significant aspect of the on-the-spot drawing is the ability to get closer to man and the world he’s made.”

“You become more than an observer; you become part of the picture emotionally. You find yourself giving up assumptions, generalizations, and beliefs once you’ve been exposed to real thing. It’s a learning process, one that never fails to alter preconceived ideas if you maintain an open mind.”

“Working in the studio may increase an artist’s knowledge of technique, but not of the world. When you’re on-the-spot, you meet people, you talk, you trade ideas and opinions. Hopefully, you grow. But most important you learn about yourself, sometimes more than you learn about your subject.”

“To me, bold committment is an emotional involvement with what you’re drawing rather than how you’re drawing it. You cannot be totally objective when you have the ability to pick and choose your subject. It stands to reason that a particular need from within precipitated your choice and your drawing is going to show it.”

“It is the emotional involvement that gives a drawing more significance than a photo of the same subject. Whether it registers in the viewer’s mind consciously or unconsciously doesn’t particularly matter – the result is the same. He’s aware that he is looking at an effort of someone with a special kind of talent who felt involved enough with what was happening to take the time and effort to record it in his own special way.”

“We’re also aware that in a minute’s time at least one photo can be taken. You needn’t have a thimble full of art knowledge to look at the average drawing and know that it could not have been executed in the same amount of time. This assumption can’t help but add to the significance that a drawing possesses.”

“To me the essence of successful reportage is capturing the fact and the meaning of a moment in time. For anyone who has found himself in the pressured position of struggling to fix that instant on paper when the situation is fugitive – sometimes hostile – it is an ideal only sometimes achieved. But it is in the attempt that I have found the joy of reportorial work.”

“If the moment is worth capturing, then the artist has the responsibility of endowing the drawing with the compassion that comes from understanding. It is in this fragile dimension the artist’s gift to the viewer is made.”

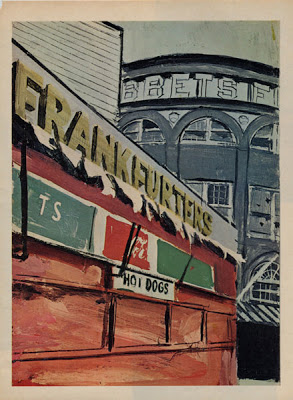

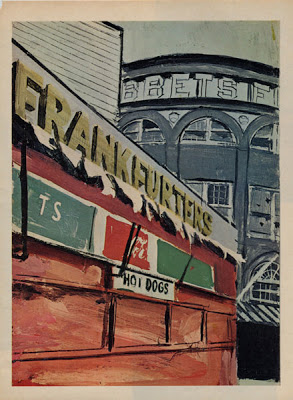

Robert Weaver

“The journalistic approach in art is nothing more complicated than a I desire to tell a story, describe an event, or illustrate a mood. The illustrator has experienced something and he desires to reproduce it. Many painters simply don’t have this desire, but an illustrator who doesn’t have it cannot very well serve the course of journalism.”

Bob Weaver doesn’t set out to “do an illustration” per se, nor does he aspire to produce a timeless work of art. His goal is basically to report; his approach – journalistic, his method – visual notations.

What he also brings along is an extraordinary ability to see and record, and he does this with an integrity that is – if one had to choose – the single most important factor of Weaver’s work.

“I think it’s absolutely essential, so far as is humanly possible, to remove all biases and preconceptions before starting a journalist assignment. We need more good reporting, fewer editorial positions. It’s far more effective to show the villain clearly than to denounce him. I’m not talking about some moral imperative to be ‘fair,’ but what makes for the maximum impact.”

Out of context with the rest of the drawing, Weaver’s line is impatient, blunt, insensitive. it’s not the kind of line you admire for its intrinsic beauty – it has little. Weaver works for the sum total, the completed drawing; and that drawing is both sensitive and beautiful, and interesting contradiction pointing out the fact that a beautiful drawing isn’t necessarily made with beautiful lines.

“Any on-the-spot sketch would provide a welcome sparkle to the printed page – lighten it. There is no doubt there are too many photos cluttering up magazines and newspapers, e.g. the public figure with a lot of out-of-focus bric-a-brac behind his left ear, or the full color photo “essay” which is all design and no content.

A second advantage would be the element of immediacy and spontaneity – rapidly disappearing from the news photo. More and more, it seems to me, the photographer and the subject are in some kind of cahoots; that is, a public figure “performs” for the camera.

Which leads to the third and most important virtue of the sketch report, which has to do with candor and truth. I think that the manipulative techniques of advertising (which is sometimes indistinguishable from the editorial elements of the printed media), the ballyhooing and self-promotion that magazines are indulging in more and more, all tend to create a credibility gap. I believe, then, that the artist could restore to the journals a visual excitement, a more personal view of events, and, finally, a more honest one.”

“You can see the unfamiliar more clearly than the familiar.”

If only a few illustrations attain this (Weaver’s) level of artistry, it is the illustrator himself who is to blame, for his approach is more often to produce something pleasing or novel, or middle-of-the-roadish. He is often more involved in developing a style that an idea.

“ There are too few illustrators who have the skill to communicate anything except very simple ideas. Magazine illustration for me is too decorative, too superficial. The challenge to the illustrator is to use artforms to reveal, to convey the gravity of and to delve into the issues of this particular time in history.

Perhaps its the fault of art schools, but there does seem to be a confusion of roles which leads the young illustrator to think he’s expected to produce works of art which are incidentally reproduced in a magazine. Nothing is more boring than this attempt to marry off the story-telling obligations of illustration with the latest school of painting. First-rate writing is having something to say – and saying it clearly. Illustration is, or should be, visual language.”

Further ObservationNick Meglin was the author of a number of books, many that deal with his years at Mad Magazine where he was an editor. A particular favorite of mine however, was The Art of Humorous Illustration, which is perhaps the first illustration book I ever owned.